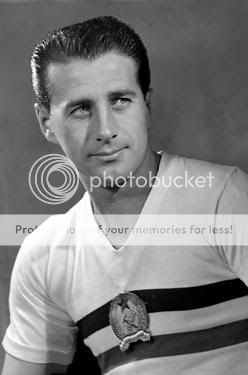

Nandor Hidegkuti

Hungary’s much-revered team of the early fifties only became the Magical, Magnificent and Mighty Magyars when Hidegkuti established himself in the team in a playmaker role as a result of his performances in the 1952 Olympics. Having been in and around the team since 1945 deployed in the main as a winger, it was his switch to playmaker that brought the best from a team of outstanding players.

Hidegkuti took a position most akin to an attacking midfielder in the modern game. It was a role employed by Hungary before, but Hidegkuti became the last piece to fit into the team’s exceptional puzzle. In a side littered with footballing giants such as Ferenc Puskás, Sandor Kocsis, and József Bozsik, it was Hidegkuti who allowed them to flourish.

His movement meant that defences struggled to pick him up without leaving huge gaps for Puskás or Kocsis to exploit. An intelligent player, he realised this and used the freedom to devastating effect.

When England played Hungary in 1953, it was Hidegkuti’s performance that left the established English tactics so bereft. Defender Harry Johnstone admitted he simply didn’t know how to mark him – he’d no idea whether to get tight and leave others in space, or gamble and leave Hidegkuti to roam where ever he wanted. Hidegkuti plundered a hat-trick and been a revelation. He’d proved that power and pace were redundant in comparison to near perfect technique married with intelligence.

Hidegkuti played throughout the 1954 World Cup and scored four times, including one goal in the brilliant semi-final with Uruguay. His entire club career was spent in Hungary so he never gained the same headlines at Barcelona and Real Madrid that Kocsis and Puskás achieved after defection. An innovator to the end, he moved into management and pioneered a 5-3-2 formation with Al-Ahly in Egypt to huge success, involved for the second time in his life with a golden generation of players.

Hidegkuti was the fulcrum of the brilliant attacking triangle that was so devastating for the Magyars. Hidegkuti laid the foundation for a position so commonplace in today’s game and allowed Puskás and Kocsis to play to their very best.

No one, really, knew what to do with him. In his quietly elegant way, he had an uncanny knack for finding open space in the center of the pitch, and from there he had manifold ways to inflict damage. His slender, upright form was easy to overlook, unlike the squat and dynamic Puskás, but he was nearly as deadly. He spent his whole career in Hungary, and consequently lacked the international fame of that Puskás quite deservedly enjoyed, especially after his move to Real Madrid. But we ought to remember Hidegkuti, and now is as good a time as any to do so. Sir Stanley Matthews would later write that he had “ravaged” the English team that day at Wembley, and called him “that sublimely gifted player.” Indeed he was. Every orchestra needs a conductor to truly bring the best out of its musicians. The brilliant Mighty Magyars had Nándor Hidegkuti.

Hungary’s much-revered team of the early fifties only became the Magical, Magnificent and Mighty Magyars when Hidegkuti established himself in the team in a playmaker role as a result of his performances in the 1952 Olympics. Having been in and around the team since 1945 deployed in the main as a winger, it was his switch to playmaker that brought the best from a team of outstanding players.

Hidegkuti took a position most akin to an attacking midfielder in the modern game. It was a role employed by Hungary before, but Hidegkuti became the last piece to fit into the team’s exceptional puzzle. In a side littered with footballing giants such as Ferenc Puskás, Sandor Kocsis, and József Bozsik, it was Hidegkuti who allowed them to flourish.

His movement meant that defences struggled to pick him up without leaving huge gaps for Puskás or Kocsis to exploit. An intelligent player, he realised this and used the freedom to devastating effect.

When England played Hungary in 1953, it was Hidegkuti’s performance that left the established English tactics so bereft. Defender Harry Johnstone admitted he simply didn’t know how to mark him – he’d no idea whether to get tight and leave others in space, or gamble and leave Hidegkuti to roam where ever he wanted. Hidegkuti plundered a hat-trick and been a revelation. He’d proved that power and pace were redundant in comparison to near perfect technique married with intelligence.

Hidegkuti played throughout the 1954 World Cup and scored four times, including one goal in the brilliant semi-final with Uruguay. His entire club career was spent in Hungary so he never gained the same headlines at Barcelona and Real Madrid that Kocsis and Puskás achieved after defection. An innovator to the end, he moved into management and pioneered a 5-3-2 formation with Al-Ahly in Egypt to huge success, involved for the second time in his life with a golden generation of players.

Hidegkuti was the fulcrum of the brilliant attacking triangle that was so devastating for the Magyars. Hidegkuti laid the foundation for a position so commonplace in today’s game and allowed Puskás and Kocsis to play to their very best.

No one, really, knew what to do with him. In his quietly elegant way, he had an uncanny knack for finding open space in the center of the pitch, and from there he had manifold ways to inflict damage. His slender, upright form was easy to overlook, unlike the squat and dynamic Puskás, but he was nearly as deadly. He spent his whole career in Hungary, and consequently lacked the international fame of that Puskás quite deservedly enjoyed, especially after his move to Real Madrid. But we ought to remember Hidegkuti, and now is as good a time as any to do so. Sir Stanley Matthews would later write that he had “ravaged” the English team that day at Wembley, and called him “that sublimely gifted player.” Indeed he was. Every orchestra needs a conductor to truly bring the best out of its musicians. The brilliant Mighty Magyars had Nándor Hidegkuti.